Tom Grant is the Treasurer for Mountain Side Day School. As a seasoned investor and business owner, Tom believes that investment advisors should use active managers for 75% – 80% of investment portfolios. He feels strongly about this but is willing to have a dialogue with the school’s investment advisor, Steve Jones. Tom asks him about the current percentage of active management in their portfolio. Steve explains, “We’re currently using both active and passive managers in the portfolio. The percentage of active managers is approximately 25% of the total portfolio because investment committee members expressed a desire to see performance closely match sector benchmarks. Also, at our first meeting, there was a consensus that we should minimize cost.” Tom looks somewhat puzzled and asks why, if they’re so heavily invested in passive solutions, they need an advisor. Steve replies, “Tom, modern portfolio theory proves that a significant amount of your returns are actually generated from the asset allocation not the manager selection. The selection of managers and your organization’s investment philosophy are important and we’re committed to working with you on both of these important aspects of managing your portfolio. But when markets are volatile and fundamentals are no longer working as expected, we find that opting for passive managers in highly efficient asset classes and using active managers in less efficient asset classes is a solid approach. But we’re happy to explore this in greater detail with you and the rest of the committee.”

This type of scenario takes place often in not-for-profit board rooms, as trustees grapple with active vs. passive investment management decisions. Most boards and investment committees—usually with the help of an investment advisor or consultant—spend time creating an investment policy statement (or reviewing an existing one). They assess the effectiveness of the asset allocation. They evaluate manager performance. They set benchmarks to measure success and oversee transactions. (For more information about benchmarks, please reference Benchmarking Basics: a Fiduciary Perspective available at Truist.com.

But they also must decide whether to use active or passive investment vehicles. This topic has been particularly noteworthy in recent years, as high correlations within domestic equity markets and coordinated activities of central banks make it increasingly difficult for active managers to beat their benchmarks.

A definition

What exactly is active vs. passive investing? A passive approach establishes the types of stocks a fund owns and then owns all of the stocks that meet those criteria. It doesn’t try to identify opportunistic investments to improve performance. While index funds aren’t the only form of passive investing, they’re certainly the most well-known. Index funds simply replicates the exact same stocks (or bonds) in the exact same proportion as those that are included in a known and measured index—such as the S&P 500® or the Russell 1000.

Active managers, on the other hand, attempt to outperform a designated market index on a risk-adjusted basis by making specific investments that exploit market inefficiencies. For example, an active manager may look for securities that are over or under valued by employing quantitative measures and attempting to anticipate long-term macroeconomic trends.

The Great Debate

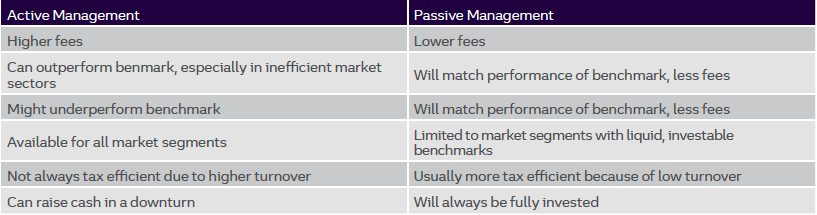

There are strong arguments to be made on both sides of the active vs. passive investing debate.

Active managers have the potential to outperform their benchmarks by overweighting and underweighting their portfolios versus the benchmark holdings, as well as by holding securities that aren’t included in the benchmark. Active managers generally charge higher fees than passive managers. Yet, despite their best efforts, active managers may still underperform their asset class benchmarks.

Passive managers generally produce performance that is very close to their benchmarks. In turn, they charge lower fees than active managers since, in most cases, their investments simply track the index’s holdings. Passive managers can’t raise cash in a market downturn to take advantage of opportunistic, tactical strategies. Their performance will almost always lag the benchmark—usually by a small amount because of fees. In general, passive investment strategies are also more tax-efficient than active strategies since they have lower turnover than the typical active manager.

Many reasons have been given for the difficulties faced by active managers, but we believe that one of the root causes stems back to the 2008 global financial crisis. Governments and central banks around the world took unprecedented coordinated fiscal and monetary policy steps to stem the crisis. In general, the net effect of these actions caused global economies to move in similar directions—a trend that continued after the crisis abated.

The fundamentals of various global sectors and stocks became less relevant. As the cost of capital for companies declined with the decrease in interest rates, there was also less differentiation between individual companies and less focus on the core businesses. This lack of differentiation led to a high correlation between individual stocks, which typically is a challenging environment for active managers. When stocks tend to all move together (high correlation) it’s difficult for an active manager focused on security selection to beat a benchmark.

As the following chart clearly demonstrates, the ability of active managers to beat there benchmarks (represented by the yellow triangles) varies greatly from asset class to asset class. In some asset classes such as large cap core, large cap growth and mid cap, very few active managers succeed. Whereas for other asset classes where information and insights aren’t as widely transparent (e.g., foreign and emerging markets, alternatives, and fixed income), active managers afford an opportunity to achieve significant outperformance.

At Truist, we believe it makes sense to use active managers in situations where there’s a reasonable likelihood of adding value on a risk-adjusted basis. Our propensity to use those managers is greater in asset classes and sectors where payoffs are appealing and odds are better than average than active managers can succeed.

What’s the right mix?

When facing this decision, not-for-profit organizations and their boards must evaluate all aspects of the issue. One major consideration is your organization’s investment philosophy. Three key concerns that guide the active vs. passive discussion are outlined below.

Less Volatility

Some not-for-profit organizations have a low tolerance for volatility. They have difficulty explaining outsized gains and losses to stakeholders. They also tend to look at portfolio performance in terms of a spending policy that supports the organization with ‘real money’ that has a dedicated purpose. In particular, a down year that negatively impacts a portfolio by 15% may not be tolerable if the organization relies heavily on investment proceeds for administration or programs. The fear of outsized losses was a common sentiment in 2008 – 2009 when domestic equity markets fell rapidly. As boards faced portfolios that sustained losses as high as 50%, it was easy to understand their predicament. But a portfolio of all passive investments can also be very volatile—as those investments will move up and down with the underlying benchmark. The only volatility that a committee will reduce by using all passive investments, is the relative performance of the portfolio to its benchmark.

If this sounds like a familiar concern, we urge your board or committee to review your investment policy statement (IPS) and decide if the current asset allocation is appropriate for your goals and risk tolerances. Indexing by itself doesn’t reduce volatility. It merely confines the performance swings to the levels experienced by the indices themselves, and eliminate the outperformance or underperformance experienced by active managers.

Simplification of the investment process

Endowment management is complex. It requires expertise, skill, and patience. Some not-for-profits may wish to minimize the investment decisions they need to make so they can focus more on their mission. But it’s important to remember that moving a portfolio to passive investments doesn’t reduce or eliminate investment-related decisions to make. Delegating investment management to an outside consultant or investment advisor is one way to minimize the burden of managing your endowment.

Sometimes a move to passive investing can lull a board or investment committee into a sense of false security—assuming the portfolio doesn’t need their full attention anymore. This is not true, as the portfolio must still be allocated among asset classes (equity vs. fixed, domestic vs. international, etc.), and then tactically rebalanced. Your IPS should be reviewed once a year to ensure that it reflects the investment objectives and risk tolerance of the organization. Oversight committees and investment advisors still have plenty of work to do after a portfolio is moved to passive vehicles.

Lower fees

Fee conscious not-for-profits often mandate the lowest fees possible on investment portfolios. Passive management is one way to achieve this goal. In addition to a consulting or advisory fee, organizations pay money managers a fund fee that covers operating expenses. Fees for an actively managed fund averaged .66% and passive funds averaged .13% according to the most recent Morningstar’s Annual Fund Fee Study.1 Committees must balance the need to minimize fees with all other investment-related factors to reach the best solution for their organization.

Our philosophy: Mission First

At Truist Foundations and Endowments Specialty Practice, our approach is to provide best-in-class asset management so that our not-for-profit clients can focus on their charitable mission. Our mandate is to deliver a competitive investment offering for our clients with both active and passive strategies across a broad selection of asset classes. While we believe in active management, our philosophy is that passive and ‘passive-plus’ options should be available as well. Our process rests upon finding those active managers that we feel have the ability to deliver the investment results we expect over the long term. While active managers as a group may struggle versus their benchmarks, we believe opportunities for outperformance do exist—especially in certain asset classes.

The decision to use active management, passive management, or a blend of both is important. It’s an evolving discussion that can be adjusted as your organization’s needs, the economy, and financial markets change. But remember; it’s only one step in the investment process.

About Truist Foundations and Endowments Specialty Practice

With a 35-year singular focus on working with nonprofit organizations, fiduciary stewardship lies at the heart of our culture. We are not merely a provider for our clients; we are an invested partner, sharing responsibility for the prudent management of your assets. Our institutional teams include professionals with extensive nonprofit expertise, who are actively engaged in the community, and able to share best practices that are meaningful to your organization.

Our practice delivers comprehensive investment advisory, administration, planned giving, custody, trust and fiduciary services to over 1,100 not-for-profits, and we administer more than $32 billion in assets for trade associations, educational institutions, foundations, endowments and other nonprofit clients.*

* As of December 31, 2020

Interested in having a deeper conversation about active and passive investment strategies?

Contact your Truist relationship manager or investment advisor or call us at 866-223-1499.